The Oral Tradition Today an Introduction to the Art of Storytelling Chapter 1 Answers

Storytelling is the social and cultural activity of sharing stories, sometimes with improvisation, theatrics or embellishment. Every culture has its own stories or narratives, which are shared as a means of entertainment, education, cultural preservation or instilling moral values.[1] Crucial elements of stories and storytelling include plot, characters and narrative point of view. The term "storytelling" can refer specifically to oral storytelling but also broadly to techniques used in other media to unfold or disclose the narrative of a story.

Historical perspective [edit]

A very fine par dated 1938 A.D. The ballsy of Pabuji is an oral ballsy in the Rajasthani language that tells of the deeds of the folk hero-deity Pabuji, who lived in the 14th century.

Storytelling, intertwined with the development of mythologies,[2] predates writing. The primeval forms of storytelling were ordinarily oral, combined with gestures and expressions.[ citation needed ] Some archaeologists[ which? ] believe that rock fine art, in addition to a part in religious rituals, may have served every bit a grade of storytelling for many[ quantify ] ancient cultures.[3] The Australian aboriginal people painted symbols which also appear in stories on cave walls as a means of helping the storyteller call back the story. The story was and so told using a combination of oral narrative, music, rock art and dance, which bring understanding and meaning to human beingness through the remembrance and enactment of stories.[four] [ page needed ] People take used the carved trunks of living trees and ephemeral media (such as sand and leaves) to record folktales in pictures or with writing.[ citation needed ] Complex forms of tattooing may likewise represent stories, with information about genealogy, amalgamation and social status.[5]

Folktales often share common motifs and themes, suggesting possible basic psychological similarities across various human cultures. Other stories, notably fairy tales, appear to have spread from place to identify, implying memetic appeal and popularity.

Groups of originally oral tales tin coalesce over time into story cycles (similar the Arabian Nights), cluster effectually mythic heroes (like Male monarch Arthur), and develop into the narratives of the deeds of the gods and saints of various religions.[6] The results can be episodic (like the stories almost Anansi), ballsy (as with Homeric tales), inspirational (note the tradition of vitae) and/or instructive (as in many Buddhist or Christian scriptures).

With the advent of writing and the use of stable, portable media, storytellers recorded, transcribed and connected to share stories over wide regions of the world. Stories accept been carved, scratched, painted, printed or inked onto wood or bamboo, ivory and other bones, pottery, clay tablets, rock, palm-leaf books, skins (parchment), bark cloth, newspaper, silk, canvas and other textiles, recorded on film and stored electronically in digital form. Oral stories go on to be created, improvisationally past impromptu and professional storytellers, as well every bit committed to memory and passed from generation to generation, despite the increasing popularity of written and televised media in much of the earth.

Gimmicky storytelling [edit]

Modern storytelling has a wide preview. In improver to its traditional forms (fairytales, folktales, mythology, legends, fables etc.), information technology has extended itself to representing history, personal narrative, political commentary and evolving cultural norms. Gimmicky storytelling is besides widely used to address educational objectives.[7] New forms of media are creating new ways for people to tape, express and consume stories.[8] Tools for asynchronous group communication can provide an surround for individuals to reframe or recast individual stories into group stories.[9] Games and other digital platforms, such as those used in interactive fiction or interactive storytelling, may be used to position the user as a character within a bigger world. Documentaries, including interactive web documentaries, utilize storytelling narrative techniques to communicate information near their topic.[ten] Self-revelatory stories, created for their cathartic and therapeutic effect, are growing in their use and application, every bit in Psychodrama, Drama Therapy and Playback Theatre.[11] Storytelling is also used as a means by which to precipitate psychological and social change in the practice of transformative arts.[12] [13] [14]

Some people also brand a case for different narrative forms being classified as storytelling in the gimmicky world. For case, digital storytelling, online and dice-and-paper-based role-playing games. In traditional office-playing games, storytelling is done by the person who controls the environs and the non-playing fictional characters, and moves the story elements along for the players as they collaborate with the storyteller. The game is advanced by mainly exact interactions, with die coil determining random events in the fictional universe, where the players interact with each other and the storyteller. This blazon of game has many genres, such every bit sci-fi and fantasy, as well as alternate-reality worlds based on the electric current reality, but with different setting and beings such equally werewolves, aliens, daemons, or hidden societies. These oral-based role-playing games were very popular in the 1990s among circles of youth in many countries earlier calculator and panel-based online MMORPG'due south took their place. Despite the prevalence of calculator-based MMORPGs, the die-and-paper RPG still has a dedicated following.

Oral traditions [edit]

Oral traditions of storytelling are plant in several civilizations; they predate the printed and online press. Storytelling was used to explain natural phenomena, bards told stories of creation and developed a pantheon of gods and myths. Oral stories passed from one generation to the next and storytellers were regarded equally healers, leaders, spiritual guides, teachers, cultural secrets keepers and entertainers. Oral storytelling came in various forms including songs, poetry, chants and dance.[15]

Albert Bates Lord examined oral narratives from field transcripts of Yugoslav oral bards collected by Milman Parry in the 1930s, and the texts of epics such as the Odyssey.[sixteen] Lord institute that a large part of the stories consisted of text which was improvised during the telling process.

Lord identified ii types of story vocabulary. The first he called "formulas": "Rosy-fingered Dawn", "the wine-night sea" and other specific ready phrases had long been known of in Homer and other oral epics. Lord, however, discovered that across many story traditions, fully 90% of an oral epic is assembled from lines which are repeated verbatim or which use one-for-one word substitutions. In other words, oral stories are congenital out of set phrases which have been stockpiled from a lifetime of hearing and telling stories.

The other type of story vocabulary is theme, a set sequence of story actions that structure a tale. Just every bit the teller of tales proceeds line-by-line using formulas, so he proceeds from event-to-event using themes. Ane near-universal theme is repetition, every bit evidenced in Western folklore with the "dominion of 3": Three brothers set out, 3 attempts are made, three riddles are asked. A theme can be equally simple as a specific gear up sequence describing the arming of a hero, starting with shirt and trousers and ending with headdress and weapons. A theme can exist large enough to be a plot component. For example: a hero proposes a journeying to a dangerous place / he disguises himself / his disguise fools everybody / except for a common person of piffling business relationship (a crone, a tavern maid or a woodcutter) / who immediately recognizes him / the commoner becomes the hero's ally, showing unexpected resources of skill or initiative. A theme does not vest to a specific story, merely may be found with pocket-size variation in many different stories.

The story was described by Reynolds Price, when he wrote:

A need to tell and hear stories is essential to the species Homo sapiens – second in necessity obviously afterwards nourishment and before love and shelter. Millions survive without love or home, almost none in silence; the contrary of silence leads apace to narrative, and the sound of story is the dominant sound of our lives, from the pocket-sized accounts of our day'south events to the vast incommunicable constructs of psychopaths.[17]

In contemporary life, people volition seek to make full "story vacuums" with oral and written stories. "In the absence of a narrative, particularly in an ambiguous and/or urgent situation, people will seek out and consume plausible stories similar water in the desert. Information technology is our innate nature to connect the dots. Once an explanatory narrative is adopted, information technology'southward extremely difficult to undo," whether or not it is true.[xviii]

Märchen and Sagen [edit]

Illustration from Silesian Folk Tales (The Volume of Rubezahl)

Folklorists sometimes separate oral tales into two chief groups: Märchen and Sagen.[nineteen] These are High german terms for which in that location are no verbal English equivalents, however nosotros take approximations:

Märchen, loosely translated equally "fairy tale(southward)" or little stories, take place in a kind of separate "once-upon-a-time" globe of nowhere-in-particular, at an indeterminate time in the past. They are clearly not intended to exist understood as true. The stories are full of conspicuously defined incidents, and peopled by rather apartment characters with niggling or no interior life. When the supernatural occurs, it is presented thing-of-factly, without surprise. Indeed, in that location is very piffling issue, generally; bloodcurdling events may take place, just with little call for emotional response from the listener.[ commendation needed ]

Sagen, translated as "legends", are supposed to have actually happened, very often at a detail time and identify, and they draw much of their power from this fact. When the supernatural intrudes (as it often does), it does then in an emotionally fraught manner. Ghost and Lovers' Leap stories belong in this category, as do many UFO stories and stories of supernatural beings and events.[ commendation needed ]

Another important examination of orality in human life is Walter J. Ong'south Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (1982). Ong studies the distinguishing characteristics of oral traditions, how oral and written cultures interact and condition one another, and how they ultimately influence human epistemology.

Storytelling and learning [edit]

Storytelling is a means for sharing and interpreting experiences. Peter Fifty. Berger says homo life is narratively rooted, humans construct their lives and shape their world into homes in terms of these groundings and memories. Stories are universal in that they tin bridge cultural, linguistic and age-related divides. Storytelling can exist adaptive for all ages, leaving out the notion of age segregation.[ citation needed ] Storytelling tin be used as a method to teach ideals, values and cultural norms and differences.[twenty] Learning is virtually effective when it takes place in social environments that provide authentic social cues near how knowledge is to be practical.[21] Stories function as a tool to pass on knowledge in a social context. And then, every story has 3 parts. Starting time, The setup (The Hero'south earth earlier the chance starts). Second, The Confrontation (The hero's world turned upside downward). Third, The Resolution (Hero conquers villain, but information technology's not enough for Hero to survive. The Hero or World must be transformed). Any story tin exist framed in such format.

Human cognition is based on stories and the human being brain consists of cognitive mechanism necessary to empathize, recollect and tell stories.[22] Humans are storytelling organisms that both individually and socially, lead storied lives.[23] Stories mirror human idea equally humans call up in narrative structures and most often recollect facts in story form. Facts can be understood as smaller versions of a larger story, thus storytelling can supplement analytical thinking. Because storytelling requires auditory and visual senses from listeners, one can learn to organize their mental representation of a story, recognize construction of linguistic communication and express his or her thoughts.[24]

Stories tend to exist based on experiential learning, but learning from an experience is not automatic. Often a person needs to endeavour to tell the story of that experience before realizing its value. In this example, it is not simply the listener who learns, but the teller who besides becomes enlightened of his or her ain unique experiences and background.[25] This process of storytelling is empowering as the teller finer conveys ideas and, with practice, is able to demonstrate the potential of human accomplishment. Storytelling taps into existing knowledge and creates bridges both culturally and motivationally toward a solution.

Stories are effective educational tools because listeners become engaged and therefore remember. Storytelling tin can be seen as a foundation for learning and teaching. While the storylistener is engaged, they are able to imagine new perspectives, inviting a transformative and empathetic feel.[26] This involves allowing the individual to actively engage in the story equally well as notice, mind and participate with minimal guidance.[27] Listening to a storyteller can create lasting personal connections, promote innovative problem solving and foster a shared understanding regarding future ambitions.[28] The listener tin then activate knowledge and imagine new possibilities. Together a storyteller and listener can seek best practices and invent new solutions. Because stories often have multiple layers of meanings, listeners have to listen closely to identify the underlying noesis in the story. Storytelling is used as a tool to teach children the importance of respect through the exercise of listening.[29] As well as connecting children with their environment, through the theme of the stories, and give them more autonomy by using repetitive statements, which improve their learning to larn competence.[30] Information technology is besides used to teach children to take respect for all life, value inter-connectedness and always work to overcome adversity. To teach this a Kinesthetic learning style would exist used, involving the listeners through music, dream interpretation, or dance.[31]

Storytelling in indigenous cultures [edit]

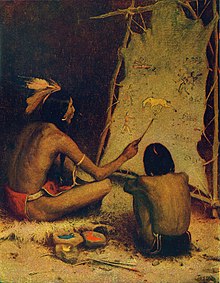

The Historian – An Indian artist is painting in sign linguistic communication, on buckskin, the story of a battle with American soldiers.

For indigenous cultures of the Americas, storytelling is used as an oral form of language associated with practices and values essential to developing 1'south identity. This is because everyone in the community can add together their own bear on and perspective to the narrative collaboratively – both individual and culturally shared perspectives have a identify in the co-creation of the story. Oral storytelling in indigenous communities differs from other forms of stories considering they are told not only for entertainment, but for teaching values.[32] For case, the Sto:lo community in Canada focuses on reinforcing children'south identity by telling stories about the country to explain their roles.[32]

Furthermore, Storytelling is a way to teach younger members of indigenous communities virtually their civilization and their identities. In Donna Eder's study, Navajos were interviewed nearly storytelling practices that they have had in the past and what changes they want to encounter in the futurity. They detect that storytelling makes an impact on the lives of the children of the Navajos. According to some of the Navajos that were interviewed, storytelling is one of many main practices that teaches children the important principles to live a proficient life.[33] In indigenous communities, stories are a way to pass cognition on from generation to generation.

For some indigenous people, experience has no separation between the concrete world and the spiritual globe. Thus, some indigenous people communicate to their children through ritual, storytelling, or dialogue. Customs values, learned through storytelling, help to guide time to come generations and help in identity germination.[34]

In the Quechua community of Highland Peru, there is no separation between adults and children. This allows for children to learn storytelling through their ain interpretations of the given story. Therefore, children in the Quechua community are encouraged to listen to the story that is beingness told in lodge to larn about their identity and civilisation. Sometimes, children are expected to sit quietly and heed actively. This enables them to engage in activities as independent learners.[35]

This pedagogy practice of storytelling allowed children to codify ideas based on their own experiences and perspectives. In Navajo communities, for children and adults, storytelling is one of the many constructive ways to educate both the young and quondam about their cultures, identities and history. Storytelling help the Navajos know who they are, where they come up from and where they belong.[33]

Storytelling in indigenous cultures is sometimes passed on by oral means in a quiet and relaxing environment, which unremarkably coincides with family unit or tribal community gatherings and official events such as family unit occasions, rituals, or ceremonial practices.[36] During the telling of the story, children may act as participants past request questions, interim out the story, or telling smaller parts of the story.[37] Furthermore, stories are not often told in the same manner twice, resulting in many variations of a unmarried myth. This is because narrators may choose to insert new elements into sometime stories dependent upon the relationship between the storyteller and the audience, making the story stand for to each unique situation.[38]

Indigenous cultures as well use instructional ribbing— a playful course of correcting children's undesirable beliefs— in their stories. For example, the Ojibwe (or Chippewa) tribe uses the tale of an owl snatching away misbehaving children. The caregiver volition ofttimes say, "The owl volition come up and stick you in his ears if yous don't terminate crying!" Thus, this grade of teasing serves as a tool to correct inappropriate behavior and promote cooperation.[39]

Types of storytelling in indigenous peoples [edit]

There are diverse types of stories among many ethnic communities. Communication in Ethnic American communities is rich with stories, myths, philosophies and narratives that serve as a means to commutation data.[twoscore] These stories may be used for coming of age themes, core values, morality, literacy and history. Very frequently, the stories are used to instruct and teach children about cultural values and lessons.[38] The meaning within the stories is not always explicit, and children are expected to make their ain significant of the stories. In the Lakota Tribe of Northward America, for example, young girls are often told the story of the White Buffalo Calf Woman, who is a spiritual figure that protects immature girls from the whims of men. In the Odawa Tribe, immature boys are often told the story of a boyfriend who never took care of his body, and as a result, his feet fail to run when he tries to escape predators. This story serves equally an indirect means of encouraging the young boys to take care of their bodies.[41]

Narratives tin be shared to express the values or morals among family, relatives, or people who are considered office of the close-knit community. Many stories in indigenous American communities all have a "surface" story, that entails knowing certain information and clues to unlocking the metaphors in the story. The underlying message of the story being told, can exist understood and interpreted with clues that hint to a sure interpretation.[42] In order to make significant from these stories, elders in the Sto:lo customs for case, emphasize the importance in learning how to listen, since it requires the senses to bring i's eye and listen together.[42] For instance, a mode in which children learn about the metaphors significant for the society they live in, is by listening to their elders and participating in rituals where they respect 1 some other.[43]

Passing on of Values in indigenous cultures [edit]

Stories in indigenous cultures encompass a variety of values. These values include an emphasis on individual responsibility, concern for the surround and communal welfare.[44]

Stories are based on values passed downwards by older generations to shape the foundation of the customs.[45] Storytelling is used as a span for knowledge and understanding allowing the values of "self" and "customs" to connect and be learned as a whole. Storytelling in the Navajo community for example allows for community values to be learned at dissimilar times and places for different learners. Stories are told from the perspective of other people, animals, or the natural elements of the earth.[46] In this fashion, children learn to value their place in the world every bit a person in relation to others. Typically, stories are used as an breezy learning tool in Indigenous American communities, and tin act as an culling method for reprimanding children's bad beliefs. In this mode, stories are non-confrontational, which allows the kid to discover for themselves what they did incorrect and what they tin do to adapt the behavior.[47]

Parents in the Arizona Tewa community, for example, teach morals to their children through traditional narratives.[48] Lessons focus on several topics including historical or "sacred" stories or more than domestic disputes. Through storytelling, the Tewa community emphasizes the traditional wisdom of the ancestors and the importance of collective equally well as individual identities. Ethnic communities teach children valuable skills and morals through the actions of skillful or mischievous stock characters while besides allowing room for children to brand meaning for themselves. By not being given every element of the story, children rely on their own experiences and not formal teaching from adults to fill up in the gaps.[49]

When children mind to stories, they periodically vocalize their ongoing attention and have the extended turn of the storyteller. The emphasis on attentiveness to surrounding events and the importance of oral tradition in indigenous communities teaches children the skill of keen attending. For example, Children of the Tohono O'odham American Indian community who engaged in more than cultural practices were able to recall the events in a verbally presented story amend than those who did not engage in cultural practices.[50] Torso movements and gestures help to communicate values and go along stories alive for futurity generations.[51] Elders, parents and grandparents are typically involved in teaching the children the cultural means, forth with history, community values and teachings of the country.[52]

Children in indigenous communities can also learn from the underlying message of a story. For example, in a nahuatl customs nearly United mexican states City, stories about ahuaques or hostile h2o dwelling spirits that guard over the bodies of water, contain morals about respecting the environs. If the protagonist of a story, who has accidentally broken something that belongs to the ahuaque, does not replace it or give dorsum in some way to the ahuaque, the protagonist dies.[53] In this mode, storytelling serves as a way to teach what the customs values, such as valuing the surround.

Storytelling also serves to deliver a item bulletin during spiritual and formalism functions. In the ceremonial use of storytelling, the unity building theme of the message becomes more important than the time, place and characters of the bulletin. In one case the message is delivered, the story is finished. As cycles of the tale are told and retold, story units tin recombine, showing diverse outcomes for a person'south actions.[54]

Storytelling research [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Y'all can help by adding to information technology. (January 2015) |

Storytelling has been assessed for disquisitional literacy skills and the learning of theatre-related terms by the nationally recognized storytelling and creative drama organization, Neighborhood Bridges, in Minneapolis.[55] Another storyteller researcher in the UK proposes that the social space created preceding oral storytelling in schools may trigger sharing (Parfitt, 2014).[56]

Storytelling has also been studied as a style to investigate and archive cultural knowledge and values within indigenous American communities. Iseke's written report (2013)[57] on the function of storytelling in the Metis community, showed promise in furthering research about the Metis and their shared communal temper during storytelling events. Iseke focused on the thought of witnessing a storyteller as a vital way to share and partake in the Metis community, as members of the community would stop everything else they were doing in order to listen or "witness" the storyteller and let the story to get a "ceremonial landscape," or shared reference, for everyone nowadays. This was a powerful tool for the community to engage and teach new learner shared references for the values and ideologies of the Metis. Through storytelling, the Metis cemented the shared reference of personal or pop stories and folklore, which members of the community can use to share ideologies. In the time to come, Iseke noted that Metis elders wished for the stories existence told to be used for farther inquiry into their culture, every bit stories were a traditional manner to pass down vital knowledge to younger generations.

For the stories nosotros read, the "neuro-semantic encoding of narratives happens at levels college than individual semantic units and that this encoding is systematic across both individuals and languages." This encoding seems to appear nearly prominently in the default mode network.[58]

Serious Storytelling [edit]

Storytelling in serious application contexts, equally e.one thousand. therapeutics, business organization, serious games, medicine, education, or faith can be referred to every bit serious storytelling. Serious storytelling applies storytelling "outside the context of entertainment, where the narration progresses as a sequence of patterns impressive in quality ... and is part of a thoughtful progress".[59]

Storytelling as a political praxis [edit]

Some approaches care for narratives as politically motivated stories, stories empowering sure groups and stories giving people bureau. Instead of just searching for the main bespeak of the narrative, the political function is demanded through asking, "Whose interest does a personal narrative serve"?[threescore] This arroyo mainly looks at the ability, authority, cognition, ideology and identity; "whether it legitimates and dominates or resists and empowers".[60] All personal narratives are seen every bit ideological because they evolve from a construction of power relations and simultaneously produce, maintain and reproduce that power structure".[61]

Political theorist, Hannah Arendt argues that storytelling transforms individual meaning to public meaning.[62] Regardless of the gender of the narrator and what story they are sharing, the functioning of the narrative and the audience listening to it is where the ability lies.

Therapeutic storytelling [edit]

Therapeutic storytelling is the human action of telling one's story in an attempt to better understand oneself or i's situation. Often, these stories affect the audience in a therapeutic sense every bit well, helping them to view situations like to their own through a different lens.[63] Noted author and folklore scholar, Elaine Lawless states, "...this process provides new avenues for agreement and identity formation. Language is utilised to conduct witness to their lives".[64] Sometimes a narrator volition only skip over certain details without realizing, only to include it in their stories during a later telling. In this way, that telling and retelling of the narrative serves to "reattach portions of the narrative".[65] These gaps may occur due to a repression of the trauma or even just a want to keep the nearly gruesome details individual. Regardless, these silences are non as empty as they appear, and it is but this act of storytelling that can enable the teller to fill them dorsum in.

Psychodrama uses re-enactment of a personal, traumatic event in the life of a psychodrama group participant as a therapeutic methodology, first adult past psychiatrist, J.50. Moreno, M.D. This therapeutic employ of storytelling was incorporated into Drama Therapy, known in the field as "Cocky Revelatory Theater." in 1975] Jonathan Fox and Jo Salas developed a therapeutic, improvisational storytelling form they called Playback Theatre. Therapeutic storytelling is also used to promote healing through transformative arts, where a facilitator helps a participant write and oft present their personal story to an audience.[66]

Storytelling as art form [edit]

Aesthetics [edit]

The art of narrative is, by definition, an aesthetic enterprise, and there are a number of creative elements that typically interact in well-developed stories. Such elements include the essential thought of narrative construction with identifiable ancestry, middles, and endings, or exposition-development-climax-resolution-denouement, commonly constructed into coherent plot lines; a strong focus on temporality, which includes retention of the past, attention to nowadays activity and protention/futurity anticipation; a substantial focus on characters and characterization which is "arguably the virtually important single component of the novel";[67] a given heterogloss of different voices dialogically at play – "the sound of the human being voice, or many voices, speaking in a variety of accents, rhythms and registers";[68] possesses a narrator or narrator-like voice, which by definition "addresses" and "interacts with" reading audiences (run into Reader Response theory); communicates with a Wayne Booth-esque rhetorical thrust, a dialectic procedure of estimation, which is at times beneath the surface, conditioning a plotted narrative, and at other times much more visible, "arguing" for and against diverse positions; relies substantially on now-standard aesthetic figuration, especially including the use of metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche and irony (encounter Hayden White, Metahistory for expansion of this thought); is often enmeshed in intertextuality, with copious connections, references, allusions, similarities, parallels, etc. to other literatures; and commonly demonstrates an effort toward bildungsroman, a description of identity development with an effort to evince becoming in character and customs.

Festivals [edit]

Storytelling festivals typically characteristic the work of several storytellers and may include workshops for tellers and others who are interested in the art form or other targeted applications of storytelling. Elements of the oral storytelling art form often include the tellers encouragement to have participants co-create an experience by connecting to relatable elements of the story and using techniques of visualization (the seeing of images in the mind's eye), and utilize vocal and bodily gestures to support understanding. In many ways, the art of storytelling draws upon other art forms such every bit acting, oral interpretation and Performance Studies.

In 1903, Richard Wyche, a professor of literature at the University of Tennessee created the commencement organized storytellers league of its kind.[ commendation needed ] Information technology was called The National Story League. Wyche served as its president for 16 years, facilitated storytelling classes, and spurred an interest in the art.

Several other storytelling organizations started in the U.S. during the 1970s. 1 such organization was the National Association for the Perpetuation and Preservation of Storytelling (NAPPS), at present the National Storytelling Network (NSN) and the International Storytelling Center (ISC). NSN is a professional organization that helps to organize resources for tellers and festival planners. The ISC runs the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN.[69] Australia followed their American counterparts with the establishment of storytelling guilds in the tardily 1970s.[ citation needed ] Australian storytelling today has individuals and groups across the country who meet to share their stories. The United kingdom's Gild for Storytelling was founded in 1993, bringing together tellers and listeners, and each year since 2000 has run a National Storytelling Week the get-go week of February.[ citation needed ]

Currently, there are dozens of storytelling festivals and hundreds of professional storytellers around the world,[70] [71] and an international commemoration of the art occurs on World Storytelling Day.

Emancipation of the story [edit]

In oral traditions, stories are kept live by being told again and again. The textile of whatever given story naturally undergoes several changes and adaptations during this process. When and where oral tradition was superseded by print media, the literary idea of the author as originator of a story'due south authoritative version changed people'due south perception of stories themselves. In centuries post-obit, stories tended to be seen as the work of individuals rather than a collective endeavour. Only recently when a significant number of influential authors began questioning their own roles, the value of stories equally such – independent of authorship – was once more recognized. Literary critics such as Roland Barthes even proclaimed the Expiry of the Author.

In business [edit]

People have been telling stories at work since aboriginal times, when stories might inspire "courage and empowerment during the hunt for a potentially dangerous animal," or simply instill the value of listening.[72] Storytelling in business has become a field in its own correct as industries accept grown, equally storytelling becomes a more popular fine art form in general through alive storytelling events like The Moth.

Recruiting [edit]

Storytelling has come up to take a prominent role in recruiting. The modern recruiting industry started in the 1940s every bit employers competed for available labor during Earth War 2. Prior to that, employers usually placed newspaper ads telling a story most the kind of person they wanted, including their graphic symbol and, in many cases, their ethnicity.[73]

Public Relations [edit]

Public influence has been role of human civilization since ancient times, but the mod public relations industry traces its roots to a Boston-based PR business firm chosen The Publicity Bureau that opened in 1900.[74] Although a PR house may not identify its function as storytelling, the house's task is to command the public narrative almost the arrangement they represent.

Networking [edit]

Networking has been effectually since the industrial revolution when businesses recognized the demand—and the benefit—of collaborating and trusting a wider range of people.[75] Today, networking is the subject for more than 100,000 books, seminars and online conversations.[75]

Storytelling helps networkers showcase their expertise. "Using examples and stories to teach contacts about expertise, experience, talents, and interests" is one of 8 networking competencies the Association for Talent Development has identified, proverb that networkers should "be able to answer the question, 'What do you do?' to make expertise visible and memorable."[76] Business organization storytelling begins past considering the needs of the audience the networker wishes to reach, asking, "What is information technology about what I practice that my audience is most interested in?" and "What would intrigue them the most?"[18]

Within the workplace [edit]

Instance of the utilize of storytelling in didactics.

In the workplace, communicating by using storytelling techniques tin exist a more compelling and effective route of delivering information than that of using only dry facts.[77] [78] Uses include:

Using narrative to manage conflicts [edit]

For managers storytelling is an important way of resolving conflicts, addressing bug and facing challenges. Managers may use narrative discourse to bargain with conflicts when direct action is inadvisable or impossible.[79] [ citation needed ]

Using narrative to interpret the by and shape the future [edit]

In a group discussion a process of collective narration can help to influence others and unify the group by linking the by to the time to come. In such discussions, managers transform problems, requests and bug into stories.[ citation needed ] Jameson calls this collective grouping construction storybuilding.

Using narrative in the reasoning procedure [edit]

Storytelling plays an important office in reasoning processes and in disarming others. In business organization meetings, managers and business organisation officials preferred stories to abstruse arguments or statistical measures. When situations are circuitous or dense, narrative soapbox helps to resolve conflicts, influences corporate decisions and stabilizes the group.[eighty]

In marketing [edit]

Storytelling is increasingly existence used in advertizement in order to build customer loyalty.[81] [82] According to Giles Lury, this marketing trend echoes the deeply rooted human need to exist entertained.[83] Stories are illustrative, easily memorable and allow companies to create stronger emotional bonds with customers.[83]

A Nielsen study shows consumers want a more personal connection in the fashion they gather information since human being brains are more engaged by storytelling than by the presentation of facts solitary. When reading pure data, only the language parts of the encephalon work to decode the meaning. But when reading a story, both the linguistic communication parts and those parts of the brain that would exist engaged if the events of the story were actually experienced are activated. Every bit a result, information technology easier to recollect stories than facts.[84]

Marketing developments incorporating storytelling include the use of the trans-media techniques that originated in the film industry intended to "build a earth in which your story can evolve".[85] Examples include the "Happiness Manufacturing plant" of Coca-Cola.[86]

Come across also [edit]

- Dramatic structure

- Story arc

- Storyboard

- Storytelling festival

- Storytelling game

- World Storytelling Day

References [edit]

- ^ "Narratives and Story-Telling | Beyond Intractability". www.beyondintractability.org. 2016-07-06. Archived from the original on 2017-07-eleven. Retrieved 2017-07-08 .

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (26 March 2015). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Routledge (published 2015). ISBN978-one-317-45937-8 . Retrieved 27 March 2021.

Myths address daunting themes such equally creation, life, expiry, and the workings of the natural world [...]. [...] Myths are closely related to religious stories, since myths sometimes belong to living religions.

- ^ "Why did Native Americans brand rock art?". Rock Fine art in Arkansas. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

[...] rock art might have played an important role in story-telling, with combined value for teaching, amusement, and group solidarity. This narrative office of rock fine art imagery is one of the electric current trends in estimation.

- ^ Cajete, Gregory, Donna Eder and Regina Holyan. Life Lessons through Storytelling: Children'south Exploration of Ethics. Bloomington: Indiana Upwardly, 2010.

- ^ Kaeppler, Adrienne. "Hawaiian tattoo: a conjunction of genealogy and aesthetics". Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Trunk. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, UCLA (1988), APA.

- ^ Pellowski, Anne (1977). The World of Storytelling. H.Westward. Wilson (published 1990). p. 44. ISBN978-0-8242-0788-5 . Retrieved 27 March 2021.

Religious storytelling is that storytelling used by official or semi-official functionaries, leaders, and teachers of a religious grouping to explain or promulgate their faith through stories [...].

- ^ Birch, Carol and Melissa Heckler (Eds.) 1996. Who Says?: Essays on Pivotal Issues in Contemporary Storytelling Atlanta GA: Baronial House

- ^ Ruediger Drischel, Anthology Storytelling - Storytelling in the Age of the Cyberspace, New Technologies, Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved January xv, 2019

- ^ Paulus, Trena M.; Marianne Woodside; Mary Ziegler (2007). ""Determined women at work" Group construction of narrative pregnant". Narrative Enquiry. 17 (2): 299. doi:10.1075/ni.17.2.08pau.

- ^ Donovan, Melissa (2017). "Narrative Techniques for Storytellers". Archived from the original on 2017-07-27.

- ^ "Stories are also growing". www.playbacktheatre.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-06.

- ^ Fuertes, A (2012). "Storytelling and its transformative bear upon in the Philippines". Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 29 (iii): 333–348. doi:ten.1002/crq.21043.

- ^ Lederman, L.C.; Menegatos, 50.M. (2011). "Sustainable recovery: The self-transformative power of storytelling in Alcoholics Anonymous". Journal of Groups in Habit & Recovery. 6 (three): 206–227. doi:10.1080/1556035x.2011.597195. S2CID 144089328.

- ^ Allen, Yard.Due north.; Wozniak, D.F. (2014). "The integration of healing rituals in group treatment for women survivors of domestic violence". Social Piece of work in Mental Wellness. 12 (1): 52–68. doi:10.1080/15332985.2013.817369.

- ^ "Oral Tradition of Storytelling: Definition, History & Examples – Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com". study.com. Archived from the original on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2017-07-08 .

- ^ Lord, Albert Bates (2000). The singer of tales, Cambridge: Harvard Academy Press.

- ^ Toll, Reynolds (1978). A Palpable God, New York:Atheneum, p.iii.

- ^ a b Choy, Esther K. (2017). Let the story practise the work : the art of storytelling for business organization success. ISBN978-0-8144-3801-5. OCLC 964379642.

- ^ Storytellingday.internet. "Oral Traditions In Storytelling Archived 2013-12-08 at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Michelle (2004). "A phenomenological evaluation: using storytelling as a primary teaching method". Nurse Education in Do. 4 (three): 184–189. doi:x.1016/s1471-5953(03)00043-ten. PMID 19038156.

- ^ Andrews, Dee; Hull, Donahue (September 2009). "Storytelling as an Instructional Method:: Descriptions and Research Question" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Periodical of Problem-Based Learning. 2. 3 (2): six–23. doi:x.7771/1541-5015.1063. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-ten-28.

- ^ Schank, Roger C.; Robert P. Abelson (1995). Knowledge and Retentiveness: The Real Story. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 1–85. ISBN978-0-8058-1446-0.

- ^ Connelly, F. Michael; D. Jean Clandinin (Jun–Jul 1990). "Stories of Experience and Narrative Research". Educational Researcher. 5. nineteen (5): 2–xiv. doi:10.3102/0013189x019005002. JSTOR 1176100. S2CID 146158473.

- ^ McKeough, A.; et al. (2008). "Storytelling as a Foundation to Literacy Development for Aboriginal Children: Culturally and Developmentally Appropriate Practices". Canadian Psychology. 49 (2): 148–154. doi:10.1037/0708-5591.49.2.148. hdl:1880/112019.

- ^ Doty, Elizabeth. "Transforming Capabilities: Using Story for Cognition Discovery & Community Evolution" (PDF). Storytelling in Organizations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-xiii.

- ^ Rossiter, Marsha (2002). "Narrative and Stories in Adult Teaching and Learning" (PDF). Educational Resources Information Center 'ERIC Digest' (241). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-xiv.

- ^ Battiste, Marie. Ethnic Knowledge and Pedagogy in Kickoff Nations Educational activity: A Literature Review with Recommendations. Ottawa, Ont.: Indian and Northern Affairs, 2002

- ^ Denning, Stephen (2000). The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN978-0-7506-7355-six.

- ^ Archibald, Jo-Ann. (2008). Indigenous Storywork: Educating The Eye, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver, British Columbia: The University of British Columbia.

- ^ Ellis, Gail and Jean Brewster. Tell it Once more!. The New Storytelling Handbook for Main Teachers. Harlow: Penguin English, 2002. Print.

- ^ Fisher-Yoshida, Beth, Kathy Dee. Geller and Steven A. Schapiro. Innovations in Transformative Learning: Space, Culture, & the Arts. New York: Peter Lang, 2009.

- ^ a b Archibald, Jo-Ann, (2008). Indigenous Storywork: Educating The Centre, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver, British Columbia: The Academy of British Columbia Press.

- ^ a b Eder, Donna (September 2007). "Bringing Navajos Storytelling Practices into Schools. The Importance of Maintaining Cultural Integrity". Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 6 (3): 559–577. JSTOR 25166626.

- ^ Vannini, Phillip, and J. Patrick Williams. Authenticity in Culture, Cocky and Society. Farnham, England: Ashgate Pub., 2009.

- ^ Bolin, Inge. (2006). Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin, Texas: The University of Texas Press.

- ^ Hodge, et al. Utilizing Traditional Storytelling to Promote Wellness in American Indian Communities.

- ^ Hodge, F.S., Pasqua, A., Marquez, C.A., & Geishirt-Cantrell, B. (2002). Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities.

- ^ a b Silko, L. Storyteller. New York, New York: Seaver Books Pub., 1981.

- ^ Hilger, 1951. Chippewa Childlife and its Cultural Background.

- ^ Loppie, Charlotte (February 2007). "Learning From the Grandmothers: Incorporating Indigenous Principles Into Qualitative Enquiry". Qualitative Health Research. 17 (2): 276–84. doi:x.1177/1049732306297905. PMID 17220397. S2CID 5735471.

- ^ Pelletier, W. Childhood in an Indian Hamlet. 1970.

- ^ a b Archibald, Jo-Ann (2008). Ethnic Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, and Spirit. Canada: University of British Columbia Press. p. 76. ISBN978-0-7748-1401-0.

- ^ Bolin, Inge (2006). Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 136. ISBN978-0-292-71298-0.

- ^ Hodge, et al. 2002. Utilizing Traditional Storytelling to Promote Wellness in American Indian Communities.

- ^ Jeff Corntassel, Chaw-win-is, and T'lakwadzi. "Indigenous Storytelling, Truth-telling and Customs Approaches to Reconciliation." ESC: English language Studies in Canada 35.1 (2009): 137–59)

- ^ Eder, Donna (2010). Life Lessons through Storytelling: Children'southward Exploration of Ideals. Indiana University Printing. pp. seven–23. ISBN978-0-253-22244-2.

- ^ Battiste, Marie. Ethnic Knowledge and Didactics in Commencement Nations Education: A Literature Review with Recommendations. Ottawa, Ont.: Indian and Northern Affairs, 2002.

- ^ Kroskrity, P. V. (2009). "Narrative reproductions: Ideologies of storytelling, authoritative words and generic regimentation in the hamlet of Tewa". Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 19: forty–56. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1395.2009.01018.x.

- ^ Pelletier, Wilfred (1969). "Childhood in an Indian Village". Two Articles.

- ^ Tsethlikai, M.; Rogoff (2013). "Involvement in traditional cultural practices and American Indian children's incidental recall of a folktale". Developmental Psychology. 49 (iii): 568–578. doi:10.1037/a0031308. PMID 23316771.

- ^ Fisher, Mary Pat. Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World'south Faiths. London: I.B. Tauris, 1997

- ^ Hornberger, Nancy H. Indigenous Literacies in the Americas: Language Planning from the Bottom up. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, 1997

- ^ Lorente Fernández, David (2006). "Infancia nahua y transmisión de la cosmovisión: los ahuaques o espíritus pluviales en la Sierra de Texcoco (México)". Boletín de Antropología Universidad de Antioquia: 152–168. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ^ VanDeusen, Kira. Raven and the Rock: Storytelling in Chukotka. Seattle [u.a.: Univ. of Washington [u.a., 1999.

- ^ "For Educators | Children'southward Theatre Company". Archived from the original on 2015-05-27. Retrieved 2015-05-29 .

- ^ Parfitt, East. (2014). "Storytelling as a Trigger for Sharing Conversations". Exchanges:Warwick Enquiry Journal. 1. two. Archived from the original on 2015-05-05.

- ^ Iseke, Judy (2013). "Indigenous Storytelling Every bit Research". International Review of Qualitative Research. half dozen (4): 559–577. doi:10.1525/irqr.2013.6.4.559. JSTOR 10.1525/irqr.2013.6.four.559. S2CID 144222653.

- ^ Dehghani, Morteza; Boghrati, Reihane; Man, Kingson; Hoover, Joe; Gimbel, Sarah I.; Vaswani, Ashish; Zevin, Jason D.; Immordino-Yang, Mary Helen; Gordon, Andrew S. (2017-12-01). "Decoding the neural representation of story meanings across languages". Man Brain Mapping. 38 (12): 6096–6106. doi:ten.1002/hbm.23814. ISSN 1097-0193. PMC6867091. PMID 28940969.

- ^ Lugmayr, Artur; Suhonen, Jarkko; Hlavacs, Helmut; Montero, Calkin; Suutinen, Erkki; Sedano, Carolina (2016). "Serious storytelling - a get-go definition and review". Multimedia Tools and Applications. 76 (14): 15707–15733. doi:x.1007/s11042-016-3865-5. S2CID 207219982.

- ^ a b Langellier, Kristen (1989). "Personal Narratives: Perspectives on Theory and Research". Text and Performance Quarterly: 266.

- ^ Langellier, Kristen (1989). "Personal Narratives: Perspectives on Theory and Enquiry". Text and Performance Quarterly: 267.

- ^ Jackson, Michael (March i, 2002). The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 36. ISBN978-87-7289-737-0.

- ^ Lawless, Elaine (2001). Women Escaping Violence: Empowerment through Narrative. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press. p. seven. ISBN978-0-8262-1314-3.

- ^ Lawless, Elaine (2001). Women Escaping Violence:Empowerment through Narrative. Columbia and London: Academy of Missouri Press. p. 123.

- ^ Lawless, Elaine (2001). Women Escaping Violence: Empowerment through Narrative. University of Missouri Press. p. 90.

- ^ Harter, 50.M.; Bochner, A.P. (2009). "Healing through stories: A special upshot on narrative medicine". Journal of Applied Advice Enquiry. 37 (2): 113–117. doi:10.1080/00909880902792271.

- ^ David Guild The Art of Fiction 67

- ^ Social club The Fine art of Fiction 97

- ^ Wolf, Eric James. Connie Regan-Blake A History of the National Storytelling Festival Archived 2010-01-20 at the Wayback Auto Audio Interview, 2008

- ^ Madaleno, Diana (2016). "10 Storytelling Festivals You Must Attend in 2016". www.brandanew.co. Archived from the original on 2017-07-xv.

- ^ "5 international storytelling festivals to check out this year and next". Matador Network. Archived from the original on 2016-09-09. Retrieved 2017-07-08 .

- ^ Lawrence, Randee Lipson; Paige, Dennis Swiftdeer (March 2016). "What Our Ancestors Knew: Teaching and Learning Through Storytelling". New Directions for Adult and Continuing Instruction. 2016 (149): 63–72. doi:10.1002/ace.20177. ISSN 1052-2891.

- ^ Bulik, Mark (2015-09-08). "1854: No Irish Demand Apply". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-01-28 .

- ^ Cutlip, Scott M. (2016-08-29). "The Nation's First Public Relations Business firm". Journalism Quarterly. 43 (2): 269–280. doi:ten.1177/107769906604300208. S2CID 144745620.

- ^ a b Phillips, Deborah R. "The transformational power of networking in today'south business concern world." Periodical of Holding Management, Mar.-Apr. 2017, p. 20+. Gale Bookish OneFile Select, https://link-gale-com.libezproxy.broward.org/apps/doc/A490719005/EAIM?u=broward29&sid=EAIM&xid=a2cece77. Accessed fourteen Feb. 2020.

- ^ Baber, Anne & Lynne Waymon. "The connected employee: the eight networking competencies for organizational success". T+D. 64: 50+ – via Gale Academic OneFile Select.

- ^ By Jason Hensel, One+. "Once Upon a Time Archived 2010-02-27 at the Wayback Auto." Feb 2010.

- ^ Cornell University. "Jameson, Daphne A Professor." Retrieved Oct 19, 2012.

- ^ "Story Telling". www.colorado.edu. 2005. Archived from the original on 2017-06-07.

- ^ Jameson, Daphne A (2001). "Narrative Soapbox and Direction Action". Periodical of Business concern Advice. 38 (iv): 476–511. doi:10.1177/002194360103800404. S2CID 145215100.

- ^ Lury, Giles (2004). Brand Strategy, Issue 182, p. 32

- ^ "The art of storytelling in 7 content marketing context questions". i-SCOOP. 2014-07-01. Archived from the original on 2017-07-05. Retrieved 2017-07-08 .

- ^ a b Plain Language at Work. "The all-time story wins Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine." Mar 25, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ By Rachel Gillett, Fast Company. "Why Our Brains Require Storytelling in Marketing Archived 2014-09-10 at the Wayback Machine." June 4, 2014. September ix, 2014.

- ^ Transmedia Storytelling and Entertainment: An annotated syllabus Henry Jenkins Journal of Media & Cultural Studies Book 24, 2010 – Issue six: Entertainment Industries

- ^ Fitzsimmons, Caitlin (March xiii, 2009). "Coca-Cola launches new 'Happiness Factory' advertisement". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

Further reading [edit]

- Beyer, Jürgen (1997). "Prolegomena to a history of story-telling around the Baltic Sea, c. 1550–1800". Electronic Journal of Folklore. 4: 43–60. doi:10.7592/fejf1997.04.balti.

- Bruner, Jerome S. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1986. ISBN 978-0-674-00365-1

- Bruner, Jerome South. Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2002. ISBN 978-0-374-20024-4

- Gargiulo, Terrence 50. The Strategic Utilize of Stories in Organizational Advice and Learning. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7656-1413-one

- Greiner-Burkert, Barbara The magical art of telling fairy tales: A practical guide to enchantment. Munich, Germany: tausendschlau Verlag. 2012. ISBN 978-iii-943328-64-6

- Leitch, Thomas 1000. What Stories Are: Narrative Theory and Estimation. Academy Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Academy Printing. 1986. ISBN 978-0-271-00431-0

- Society, David. The Art of Fiction, New York: Viking, 1992.

- McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks. 1997. ISBN 978-0-06-039168-3

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storytelling

0 Response to "The Oral Tradition Today an Introduction to the Art of Storytelling Chapter 1 Answers"

Postar um comentário