Why Was Stymi and Bruno the Most Interesting Failures in Language Arts

In March 2021, Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the heaven is low and heavy) (Figure 1), an installation by the artist David Lamelas, was dismantled. Consisting of a trapezoidal steel construction under which three rows of viii trees are planted, the work has occupied a spot on the gravel lawn on the east side of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA) for nigh three decades. Yet, as the KMSKA is entering the final phases of its years-long renovation, Lamelas' work was deemed to be in conflict with the planned pattern. Following the obstructive mandate of the Flanders Heritage Agency, January Jambon, the Flemish Prime number Government minister and Minister of Civilization, withdrew his initial back up, shifting all responsibleness to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp (One thousand HKA), which was gifted the work by the artist in 2011. Lamelas sent a letter to Jambon, stressing the importance of the work and the responsibleness of the Flemish government to save it. The aforementioned letter carried the back up of over 900 signatories from an international community of art professionals. Despite this weighty telephone call, M HKA's director Bart de Baere did not even so take physical plans to secure the work's preservation, condemning information technology to an uncertain hereafter.1

Quand le ciel bas et lourd, titled after Charles Baudelaire'southward Les Fleurs du Mal, was installed in 1992 as function of the exhibition America: Helpmate of the Dominicus—500 Years of Latin America and the Depression Countries at the KMSKA. The prove examined the cultural, economic and political exploitation of indigenous Americans past European forces, and its long, often violent projection of colonization and erasure. Characteristically, Lamelas' installation does not literally express these histories, nor is it reducible to them. Instead, its semantic plurality seems to be key to the work's poetics of repression and conveyance of promise; while some of the trees have grown over the structure, virtually hiding information technology, others have died due to a lack of light and water.

This article uses Lamelas' piece of work as a lens to examine 2 aspects of contemporary art and history in Flanders. Firstly, it foregrounds the complex, transnational heritage that Lamelas' work presents. The article considers Lamelas' works and exhibitions made in Kingdom of belgium in the tardily 1960s and 70s, and again in the early 1990s, exploring his relations to the local artistic avant-garde. Secondly, the text frames Quand le ciel bas et lourd and America: Helpmate of the Sunday within cultural and political developments in Flanders in the early 1990s. The piece of work and show were realized within months of "Black Dominicus", the notorious 1991 federal ballot that marked the rise of the Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) and, with it, radical-right nationalism in Flemish region. Together these sections illuminate how Lamelas' piece of work might claiming monolithic formations of Flemish art.

1. Lamelas, Antwerp–Brussels

It was 1:55 p.m. in the Belgian city of Brussels when Maria Gilissen, photographer and Marcel Broodthaers' wife2, took a black-and-white photograph of artist David Lamelas walking through a busy thoroughfare (Effigy ii). The details of the city tin be seen in the cobblestone street, tram train tracks or backdrop of commercial buildings, such as Leonidas the enduring Belgian chocolate visitor or the no longer extant Banque de Bruxelles. This epitome is one of ten taken past Gilissen for Lamelas' piece of work Antwerp–Brussels (People + Fourth dimension) from 1969 (Figure 3). The artwork was to photographically document individual figures in various locations in Brussels or Antwerp at specific times. In Brussels, Lamelas got a picture of art collector Herman Daled at 1:50 p.m., artist Marcel Broodthaers at 2:xiii p.m. and Gilissen at two:twoscore p.m. In Antwerp, gallerist Anny De Decker is photographed at i:20 p.m. and her partner artist Bernd Lohaus3 at 1:30 p.m., collector Isi Fiszman at 4:30 p.m., curator Kasper König at three:xxx p.1000., his partner Ilka Schellenberg at 2:45 p.m. and creative person Panamarenko at 3:50 p.m. Merely put, these individuals were friends and professional assembly of Lamelas. A group of local figures emerging in the Belgian fine art world that the artist had come to know and piece of work with regularly since moving to Europe in 1968, they constituted what De Decker called the "Belgium grouping", which achieved an international reputation as an agile "unconstituted, ephemeral and natural" circle in the contemporary art scene (De Decker and Lohaus 1995, p. 32; Buren 1995, p. 103). In retrospect they are significant for their key role in the development of post-war avant-garde art in Kingdom of belgium and internationally. Therefore, it is interesting that Lamelas, an artist from Argentine republic who started studying at St. Martin's School of Art in London in 1968, would include himself in this series of photographs.

This is particularly so when we wait at similar fourth dimension pieces past Lamelas from 1969–1970, where his presence is conspicuously absent: Time as activity (Dusseldorf) (1969), Gente di Milano (1969) and Moving picture 18 Paris IV. 70 (also known as People + Time: Paris) (1970).4 In each of these works Lamelas turns the camera towards the urban center in a documentary manner capturing its people and action in fragments of time. However, as much as they were meditations on fourth dimension, they were likewise profiles of a place. In his words, Lamelas claimed to "advisable the social and spatial life of the city." (Lamelas [2016] 2017, p. 167)Antwerp–Brussels is equally "site-specific", a term used by Lamelas to depict the way it incorporated the physical and social conditions of a item location as integral to the artwork. The cities of Antwerp and Brussels are not but determined by their geographic and urban structures, but also their social relations and, more specifically, artistic network. Lamelas' insertion of himself into this configuration reveals the extent to which he identified with these locations and contexts, and even imagined himself as a component of them. The photographic series certainly attests to Lamelas being there and having a place inside "Antwerp-Brussels" in the year 1969.

In the previous year Lamelas left Argentina for the 34th Venice Biennale to produce Function of Information nigh the Vietnam State of war at Three Levels: Visual Epitome, Text and Audio (1968) for the Argentine Pavilion. The installation consisted of a drinking glass enclosed part, complete with a teletype machine that transmitted up-to-engagement data well-nigh the Vietnam War from the Italian wire service (Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata), which was then read in several different languages by a alive attendant sitting at the desk and documented with an audiotape recording over the grade of the exhibition.5 As Lamelas recalls, a coincidental chat unfolded with Marcel Broodthaers who showed interest in the work. Their initial connection resulted in meeting Anny De Decker, Bernd Lohaus and Isi Fiszman, who were also present in Venice, and De Decker's immediate invitation to present his work for her Antwerp-based gallery Wide White Space at Prospect 68 at the Städtische Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf.vi

This first come across precipitated a longstanding and dialectical human relationship betwixt Lamelas and conceptualism in Kingdom of belgium that materialized in artistic collaborations, exhibitions and broad affiliations. From Venice, Lamelas moved to London to study at Saint Martin's School of Art and ultimately stayed until 1974, only frequented the cities he had established connections with, primarily Brussels, Antwerp and Paris.7 In Belgium, Lamelas became function of a roster of European and American conceptual artists represented by the pioneering avant-garde gallery Broad White Space. He exhibited repeatedly during the gallery'south lifetime between 1968 and 1976 at both the Antwerp and the short-lived Brussels' location.8 Additionally he was included in the gallery's exhibitions at Prospect 68 and 69, with the installation Assay of the elements past which massive consumption of information takes place (1968) and flick Fourth dimension as Activity (Düsseldorf) (1969). From Jan to Feb 1970, Lamelas was given a solo evidence which featured Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) (1969), Time as Activity (1969) and two other photographic series. Antwerp (1969) consisted of three color photographs of the cityscape and timestamps of 11:42 p.g., 1:48 p.1000. and 4:30 p.thou., respectively. Brussels (1969) similarly indexed the everyday activities of the city in three colour photographs. In the absenteeism of a central effigy, Lamelas concentrates on the urban details: motor traffic, commercial stores, tree-lined boulevards, eclectic architecture, grayness skies and bearding pedestrians. These three works were recurrent in Lamelas' exhibitions at the gallery. Broad White Space was also key in the development of his piece of work from the 1970s in the mode De Decker and Lohaus supported the making and presentation of Lamelas' films Cumulative Script (1972), To Pour Milk into a Glass (1972) and Desert People (1975). Autonomously from his collaborations with Wide White Space, Lamelas exhibited at the gallery of G. Poirier dit Caulier, former owner of X-1 Gallery in Antwerp, in 1974 and at the Palais des Beaux-Arts Brussels in 1976.

Past the belatedly 1960s Brussels and Antwerp were emerging every bit of import artistic centers for avant-garde fine art supported by the very network of curators, gallerists and collectors photographed by Lamelas. In addition to Wide White Space'south opening in 1966, art spaces dedicated to conceptual art emerged over the course of the belatedly 60s and early on 70s, notably in Antwerp the gallery Kontakt opened in 1964, X-One Gallery and the experimental platform A 37 90 98 in 1969, then the public art heart Internationaal Cultureel Centrum in 1970. In Brussels, MTL opened in 1969 and the 2d location for Wide White Space in 1973.9 On a broader, international scale these two cities were coordinates within a changed geography of art following Globe State of war II. As many scholars have pointed out, a region known as the "artistic triangle" encompassing Antwerp and Brussels in Belgium, Amsterdam in holland, and Cologne and Düsseldorf in Federal republic of germany proved to be an active, transnational space that facilitated the development of conceptual fine art in Europe and abroad (Decan 2016).x De Decker and Lohaus in item envisioned Broad White Space equally an international gallery, which had a particular orientation towards contemporary artistic trends surfacing beyond Europe and the U.s..11

In this sense, the ambitions of Wide White Space and Lamelas were similar as both cultivated a modality of cosmopolitanism. Curators, from Inés Katzenstein to Kristina Newhouse, have described Lamelas as a nomad and perpetual greenhorn and this ultimately determined his piece of work. For Katzenstein, Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) is evidence of Lamelas' "true cosmopolitan" character, which she defines as "an orientation, a desire to mingle with the Other" as well every bit "a stance of aesthetic and intellectual openness vis à vis diverse cultural experience" and "a familiarization with dissimilar cultures." (Katzenstein 2006, p. 80)12 The significance of the piece of work to concretize modes of cosmopolitan and vernacular belonging had implications for Lamelas, peculiarly in terms of the evolution of his work, the development of important professional networks and a level of integration into the local artistic scene (that would later influence his return in the 1990s). In plow, Antwerp, Brussels and its artistic circles are equally rendered as open up and transnational.

Marcel Broodthaers, like Wide White Space gallery, was intrinsic to Lamelas' ties to Belgium'south artworld. A number of photographs from Broodthaers' archives evidence the 2 artists side by side in a display of friendship that developed from their chance meet in Venice in 1968. One of the terminal photographic records of them before Broodthaers' death in 1976 is a series of three black-and-white images of the artists together in Berlin in 1975. They are pictured walking downwards an empty street, appearing closer to the photographic camera with each subsequent shot. In the last photo, they are in the foreground as Lamelas glances at Broodthaers. The photographs, taken by Maria Gilissen, are preparatory images from an unfinished collaborative film projection.13 This slice tin can be read as an extension of Lamelas' filmic and photographic studies that fused fourth dimension, place and people. Every bit much equally Berlin was a main field of study, there is also continuity with Lamelas' involvement in representing his friends, evinced in Brussels–Antwerp (People + Time) and once more in 1973 when he photographed his social circle for London Friends (1973). The city's topography was once more both spatial and social, in the sense of artistic connections situated in urban space or in specific places where creative collaborations emerged and concepts developed. Ultimately, Broodthaers and Lamelas' unrealized work demonstrates the extent to which their friendship was a basis for artistic collaboration and influence that would shape their work over the years.

In similar terms Broodthaers would involve his social circle in the performance of his fictive establishment Musée d'Fine art Moderne, Département des Aigles in a series of open letters. Writing from the position of Museum Director, Broodthaers authored a number of statements as letters, often addressed to friends, nevertheless distributed publicly. In i alphabetic character from 31 October 1969 the artist addressed "mon cher Lamelas" (my love Lamelas) in what Benjamin Buchloch argued was the "well-nigh pointed critique of the conceptual motion to be articulated by 1 of [its] artists", referring to Broodthaers' position that the "reality of the text" was not synonymous with "the real text" (Buchloch 1987, p. 97). Despite Broodthaers' apparent critique, the artist mimics the numerated sequence of statements typical of conceptual artists' piece of work, such equally Lawrence Weiner'due south Statement of Intent (1968) and Sol LeWitt's Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969), too as the prevalent culture of exchange amidst conceptual artists and critics.xiv His letter of the alphabet to Lamelas echoes several mentions to the artist, including ane open letter written from Antwerp on 11 Oct 1968 in which Broodthaers lists a serial of "art recommendations", including Lamelas, amidst 19th century French caricaturist J.J. Grandville, Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and 20th century Belgian Surrealist artist René Magritte—Ingres and Grandville beingness ii artists that he represented in his Musée d'Art Moderne (Broodthaers 1968).

As many scholars take noted, Broodthaers was enchanted by 19th century French art and literature, best exemplified in the artist's references to painters Ingres and Courbet in his Musée d'Art Moderne and poets Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire in his exhibitions, films and books. His affinity to verse is no surprise given that Broodthaers was a poet until he seemingly abandoned this form to make art in 1964. Equally Rachel Haidu has remarked, Broodthaers' use of French literature verged on a complex relationship to history, contemporaneity, authorship, identity, quotation and aura (Haidu 2010). In 1969–1970 Broodthaers would nourish a seminar on Baudelaire in Brussels given past French Marxist philosopher Lucien Goldmann, which became a source for his book Charles Baudelaire. Je hais le movement qui déplace les lignes (1973) and likely influenced several of Broodthaers' films made in 1970 that use Baudelaire'due south life and poetry as its subject.

Most twenty years after Lamelas would gesture towards Baudelaire in the making of Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the sky is low and heavy) (1987–1992)—a public installation for the exhibition America: Bride of the Sun—500 years of Latin America and the Low Countries at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA). Lamelas' participation in the testify marked his return to Belgium, afterward a period of distance and relative disengagement since moving to Los Angeles in 1976.fifteen This time Lamelas moved to Belgium, living at that place intermittently from the tardily 1980s to the late 1990s, which coincided with a retrospective interest in the country's post-state of war avant-garde.16 During these years in Belgium, he formed a network with a new generation of curators and gallerists, which catalyzed a series of exhibitions of Lamelas' work in the country. In 1991, for case, Lamelas had a solo exhibition at Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, a gallery run by Broodthaers' only daughter, Marie-Puck. The testify, titled Lavandula, Labiatae, Lamiales, included different species of lavender shrubs planted across the gallery floor equally well as works that reveal a sustained interest in nature, plant life and its effects when placed within or against spatial structures, like in the cartoon and maquette of Tree inside a drinking glass house (1990) (Effigy four). A later work, Span between two copse (1996), made for an outdoor grouping exhibition in a minor town in the province of Antwerp, Zoersel, linked ii trees with a steel structure and is another instance of Lamelas' visual linguistic communication in the 90s.

Quand le ciel bas et lourd, Lavandula..., and Bridge between 2 copse exemplify Lamelas' engagements with fourth dimension, large-scale sculpture, site-specific installation, and organic environments in the early on 1990s. As Dirk Snauwaert, curator of Lamelas' 1997 retrospective New Refutation of Time noted, Lamelas' work since the 1980s demonstrated a revived "interest in the conventions of space and compages through site-specific public works that centered on urban landscape and oppositions between nature and artifice."(Snauwaert 1997, n.p.) Moreover, the notions of environment, site, and historical context besides inform Lamelas' work on a more biographical and semantic level. After all, Lamelas admits that Broodthaers was influential in his decision to quote Baudelaire's "Spleen IV" in Les Fleurs du Mal (1861).17 Lamelas evoked Baudelaire's rather dour poetic representation of melancholy elicited in "the depression and heavy sky" and its sense of spatial confinement, of enclosure, oppressive weight and darkness. This status is mirrored in the work's 3 rows of sycamore trees shielded past a large-scale trapezoidal structure of steel that over time would stymie their natural growth. Similar Baudelaire's poem, Lamelas' work is the "lid/ over the mind tormented by disgust … where Promise,/ defeated, weeps, and the oppressor Dread/plants his black flag on my assenting skull." (Baudelaire 1968, p. 88). As the personification of hope is restricted, causing its slow demise and potential decease, Lamelas' trees undergo a similar process of immobility, deformation and sometimes death. While Baudelaire was referring to a depressed condition inherent of modern life, Lamelas draws a parallel to the and then-called "discovery of America" thematized in KMSKA'due south exhibition.

ii. America: Bride of the Sun

In the context of the large-scale exhibition America: Bride of the Lord's day, Lamelas' public artwork operates as a poetic apologue of the European conquest of the Americas—a vehement meet that the exhibition explicitly sought to explore. The year 1992 was the quincentenary of the so-chosen "discovery" or "conquest" of the Americas by Columbus under the Spanish crown. Sponsored by Unesco, a serial of events was initiated beyond European and American museums that meant to reflect upon this historical moment and the subsequent coming together and cross-fertilization of peoples and cultures.xviii The Flemish Community'southward Department of External Affairs seized the opportunity to devise an exhibition and book project about the relation betwixt Flanders and the Americas. The exhibition was set in Antwerp, a city that was a primary trading port with the Americas and habitation to the most prominent Flemish artists, whose work was exported to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries. More than specifically, the arrangement used the KMSKA, an institution housed in a stately neoclassical building in the city's Zuid district and administered by the Flemish Community since 1982.xix

Central to the exhibition was the part of Flemish fine art in facilitating the imposition of cultural, political and economic values from Europe to the Americas. Since Flanders, or the South-Netherlands, brutal under Spanish rule in the mid-16th century, i thesis of the exhibition was that Flemish paintings, engravings, drawings and sculptures depicting Catholic scenes and motifs were used by the conquista in the process of Christianization and colonization, guiding and in fact fostering cultural, political and economic suppression. In plough, the show demonstrated the cross-pollination of cultures in Latin American art, where ethnic motifs and materials were married to Western image traditions, and how art from Latin America had been imported to Europe. This dual thesis, developed past KMSKA curator Paul Vandenbroeck and Catherine de Zegher, then the director of the art eye Kanaal in Courtrai, meant to identify the relation between Flandes y América as complex and multisided. Additionally, the exhibition ready out to develop a cultural and geopolitical perspective on Flemish art's iconography, materiality and form.

With some 400 works spread across 24-odd spaces on the museum's ground floor, America: Bride of the Dominicus was an ambitious endeavor (Figure v). The exhibition was structured in two segments. The first, "Europe's Gaze," included artworks and artifacts that immune re-examining diverse levels—religious, scientific, economic, and sensorial—in the acquisition of the "new" world. On display were nautical instruments, Columbus' reports of his travels, atlases and maps, natural history books, paintings depicting Catholic missionaries and conversion processes, and an 18th-century still life showing imported goods (such every bit tobacco, tomatoes or chocolate). Here, the exhibition too focused on the pivotal part played past Flemish fine art in the production and dissemination of a "universal" Baroque across the Atlantic, mainly the excessive, counter-Reformative paintings resulting from the schoolhouse of Rubens. The second segment, "Labyrinthus Americanus," examined how Latin American art and culture responded to discovery and colonization, notably how European art and faith was acculturated and enmeshed with local beliefs and customs. This section addressed types of syncretism in paintings and documents showing indigenous men and women (as a representation of gender and role patterns); devotional art mixing Cosmic themes with indigenous motifs and materials (suggestive of cultural cantankerous-pollination); and images of fights between angels and devils (a genre associated with Latin American popular civilization and an allegory of the boxing with the colonizer). The anonymous oil painting Virgen del cerro (The virgin of Mount Potosí, 18th century), for example, depicts the Virgin Mary as flanked by a lord's day and moon, symbols mutual to Inca and European art, and equally a mountain evoking an Inca "earth mother" watching over a pre-colonial village at her feet. The paradigm is too suggestive of economic exploitation, since the Potosí mountain was a natural source mined for silver. The painting, which was exemplary of the European interest in the Americas and the labyrinthine result of their discovery, tellingly featured on the exhibition catalogue's embrace.

Scattered across these thematically structured rooms were contemporary artworks by Latin American artists. In charge was Catherine de Zegher, who in preparation of the exhibition had visited Mexico, Venezuela and Cuba in the aim of tracking modern and contemporary artworks echoing the theme of the exhibition. De Zegher included some xx modern works and installations by 24 contemporary artists, some existing and others deputed. These works meant to describe out the long-standing aftermath of America's colonization, including the enduring entanglements of ethnic and Western influences in art and popular culture. Many of its artists, working across various mediums, are now recognizable figures in global histories of art, and more specifically fine art from Latin America. From Ana Mendieta to Cildo Meireles, de Zegher showcased key artists in the field of Latin American fine art working since the 1950s and 60s, which, by the 1990s, with the emergence of global discourses of art and multiculturalism, started to receive greater attending. Moreover, the inclusion of gimmicky art meant to transport the exhibition's historical themes into the present, speculating, for instance, on how Western capitalism and Idiot box images piece of work to bring about a contemporary class of imperialism.

Equally critics noted, America: Helpmate of the Sun offered a nuanced, plural perspective upon colonization and its aftermath in contemporary Latin American art. In presenting Europe's oppression of the Americas in conjunction with its impact on local fine art and culture, and in mixing art with contemporary works in thematic sections, the show was lauded for its avoidance of both Eurocentric perspectives and Western historiographical models based upon chronology. Art critic Jean Fisher wrote how the "convergences, recurrences, and ruptures" in America: Bride of the Sunday invited viewers "to face [their] ain Latin American imaginary in its accumulation and cross-referencing of signs."(Fisher 1992, p. 99)twenty Fisher moreover noted how such ideas of decentering were absent from exhibitions such as "Primitivism" in Twentieth Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (MoMA, New York, 1984) and Magiciens de la terre (Centre Georges Pompidou & Musée de la Villette, Paris, 1989), which ignored "the context shaping the piece of work and its meanings, not to speak of the sociopolitical and historical formations of the West's relations with those others who accept produced them."(ibid.) Moreover, critics found America: Bride of the Sun made explicit the contradictory position of the hegemonic, Western museum in hosting such discourse. The image, formulated past de Zegher in the catalogue and interviews, that installations by Latin American artists on the ground floor were "weighed down" by the exhibition of Flemish Masters and a "universal idiom of painting" exhibited on the flooring above, demonstrated an awareness of how the 19th-century museum of the KMSKA was "exposed" as being itself a bearer of the hegemonic values that the exhibition sought to gainsay. Some other facet of institutional criticism arose when de Zegher accused KMSKA director Lydia Schoonbaert of despotism, when the director had drastically altered 3 contemporary artworks on the grounds of their including organic materials, which could supposedly attract hazardous insects to the KMSKA's collection.21

While some critics remarked upon the heavy-handedness of the exhibition and the role of artworks every bit pieces of "evidence" in its hypothesis, overall they valued how the curators, informed by postcolonial theory, spoke in a dialectical natural language about issues like the eye and the periphery, the West and its Other.22 On the other paw, critics failed to find how this same decentering and promulgation of cultural exchange reverberated with then-current political and civilization–political weather condition in Flemish region. After all, America: Bride of the Sun opened but a few months post-obit "Black Sunday," the notorious federal election of 24 November 1991 that marked the historical rise of Vlaams Blok (at present Vlaams Belang), Flanders' radical-right nationalist political party.

Established in 1978 every bit a right-wing offshoot of the Volksunie, a socially democratic Flemish-nationalist party, Vlaams Blok had equally its fundamental tenet the institution of Flanders equally an independent state. Only in the late 1980s, yet, when the party hardened its entrada and began targeting Northward African and Turkish migrants, did it succeed electorally. Vlaams Blok saw a dramatic surge in voters in both the municipal elections of 1988 and the European elections of 1989, yet the biggest success came in the fall of 1991, when, in the voting commune of Antwerp, more than 20 pct voted for Vlaams Blok and the party obtained 12 seats in the Belgian Senate. Thanks to the nativist slogan "Eigen Volk Eerst" ("Our own people first") and a provocative campaign image—a giant battle glove supposedly targeting the grouse and incompetent politicians (but widely understood equally a call to arms against migrants)—"Blackness Sunday" is associated with the rise of far-correct nationalism, racism, and nativism in Flanders alike. In June 1992, when Vlaams Blok published its 70-point plan for solving "the migrant problem," the party openly confessed to its racial and discriminatory calendar.23 Equally radio journalist Jos Bouveroux wrote, "priority is given, not to our own people—a feature of all nationalisms—merely to a right-fly, totalitarian state." (Bouveroux 1999, p. 240).24

While it is important to stress that Flemish nationalism is neither xenophobic nor right-fly per se, it is also crucial to admit their parallels. Both nationalism and xenophobia are premised upon the notion of a "natural" and essential distinction between different cultures and groups of people, between "ane's own" and Others, which makes nationalism attractive as a more than publicly accepted form of social bigotry (Reynebeau 1995, p. 265) Today, both Vlaams Belang and Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (Due north-VA), the conservative Flemish-nationalist party that arose from the vestiges of the Volksunie in 2001, speak of a Western Leitkultur equally the grounds for their disregard of multiculturalism and promotion of homogenous cultural entities.25

The decentering and syncretism presented in America: Helpmate of the Sun, even if indirectly or invariably, can be seen every bit responding to this upsurge of far-right nationalism and racism in Flanders. Iii features substantiate this claim. Firstly, the testify's catalogue and printing texts suggest that the 500th anniversary of Columbus' "discovery" of America served to address contemporary political developments in Belgium and concurrent discussions almost intercultural relationships. In the book's introduction, for instance, Vandenbroeck speaks of different cultures and the thought of the nation as a cultural and political whole in terms that resonate with the then-current political condition of Kingdom of belgium and nationalism in Flanders:

How, and then, to speak of a different culture, or even more difficult, of a patchwork of cultures within 1 geographical whole? Every arroyo and option of field of study will behave something random in it, something based upon desires that are difficult to pin downwards. Every attempt to grasp the "cadre" or "essence" of a particular culture turns out to exist a pious wish: the observer selects a hitting category, thought, or structure, which fits his conceptual framework. Additionally, what concerns the contact between "ane's ain" and "foreign" culture: one rapidly tends to overestimate the role of the former.

Further on, Vandenbroeck notes that along with the taxonomies of the natural sciences, the 16th century saw the rise of racist theories, according to which "other" cultures needed to be fought, destroyed, and, possibly, idealized. This raising of sensation for xenophobia and for the echoes between past and present in the bear witness is also described by de Zegher in an unpublished press text issued by the Flemish Community:

Within the political constellation of Europe, faced with rising nationalism and growing racism, one might wonder if information technology is still—as if it always was—possible to develop strategies of multicultural art globe politics and to expect political consequences emerging from those exhibitions. We have tried to construct a decentered exhibition projection, which does more than than only expand the territory of Western hegemony or art world investment. Additionally, this should be clear in the very construction of this exhibition and the display of the contemporary works (installations) among the former historical paintings and sculptures.

Secondly, the catalogue subtly attests to quarrels about the championship between the curators and KMSKA's director and senior staff. De Zegher initially proposed the Spanish–Dutch Ver América, which means both "to run into America" and "(culturally) far America." Manager Lydia Schoonbaert and senior curator Erik Vandamme, still, were opposed to this predominantly Castilian sounding championship on the grounds of its being supposedly pretentious and potentially misunderstood by the public. In a baking note entitled "Ver gezocht en ver van goed" ("Far-fetched and far from good"), Vandamme wrote that "the title's subtleties, which generate intellectual pleasance for the in-oversupply balky to clichés and striving for ingenuity, are completely lost on the average Joe."(Vandamme 1991)28 As an alternative, Vandenbroeck proposed inti-coya (Quechua for sun-moon, as an allegory for the contradiction Europe-America), or no title at all, simply two strong images. The former was also rejected as sounding likewise "foreign" (KMSKA 1991b).29 These objections and with it the implied schism between an elitist squad of curators and an uneducated Flemish public receive an uncanny echo when seen in the light of the far-right nationalism so on the ascension. Indeed, the contrast between the curatorial ambitions and the championship was and so great that both Vandenbroeck and de Zegher stressed their dissatisfaction in the catalogue—the onetime in his introduction, the latter in "Ver América," an interview between de Zegher and art critic–historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh.

Thirdly, America: Bride of the Sun contrasted with the initial project "Flandes y América," gear up by the Flemish Community in collaboration with professor and historian Eddy Stols. This project proposed an exhibition spread across five chapters that would present "the Flemish influence in the development of America, notably the southern function starting from Mexico," from "cultural and technical collaboration" to agriculture and industry (Verstraeten 1989). The archives hold only outlines of the project, but these documents nevertheless paint a laudatory picture of Flemish colonial involvement, an all just nuanced story. In dissimilarity, Vandenbroeck proposed a project in which the oppressive features of the "discovery" of the Americas and the Eurocentric viewpoint would be acknowledged (the outset segment), and where this view would be divorced from a loose, multifarious exploration of the Latin-American "labyrinth" (the second segment). De Zegher backed this alternative, suggesting how "the influence of the Netherlands" is not a workable criterion for contemporary fine art, whose internationalism is central (KMSKA 1991c). That is, if the quincentenary offered the Flemish Community an opportunity to highlight the influence of Flemish fine art upon the New Earth, the exhibition somewhen painted a historically and politically more nuanced picture show. Tellingly, Stols from circa 1991 onwards was no longer included in the meetings yet claimed moral and intellectual holding over the original project (thus adding to the aforementioned debates about the exhibition's title) (KMSKA 1991d).

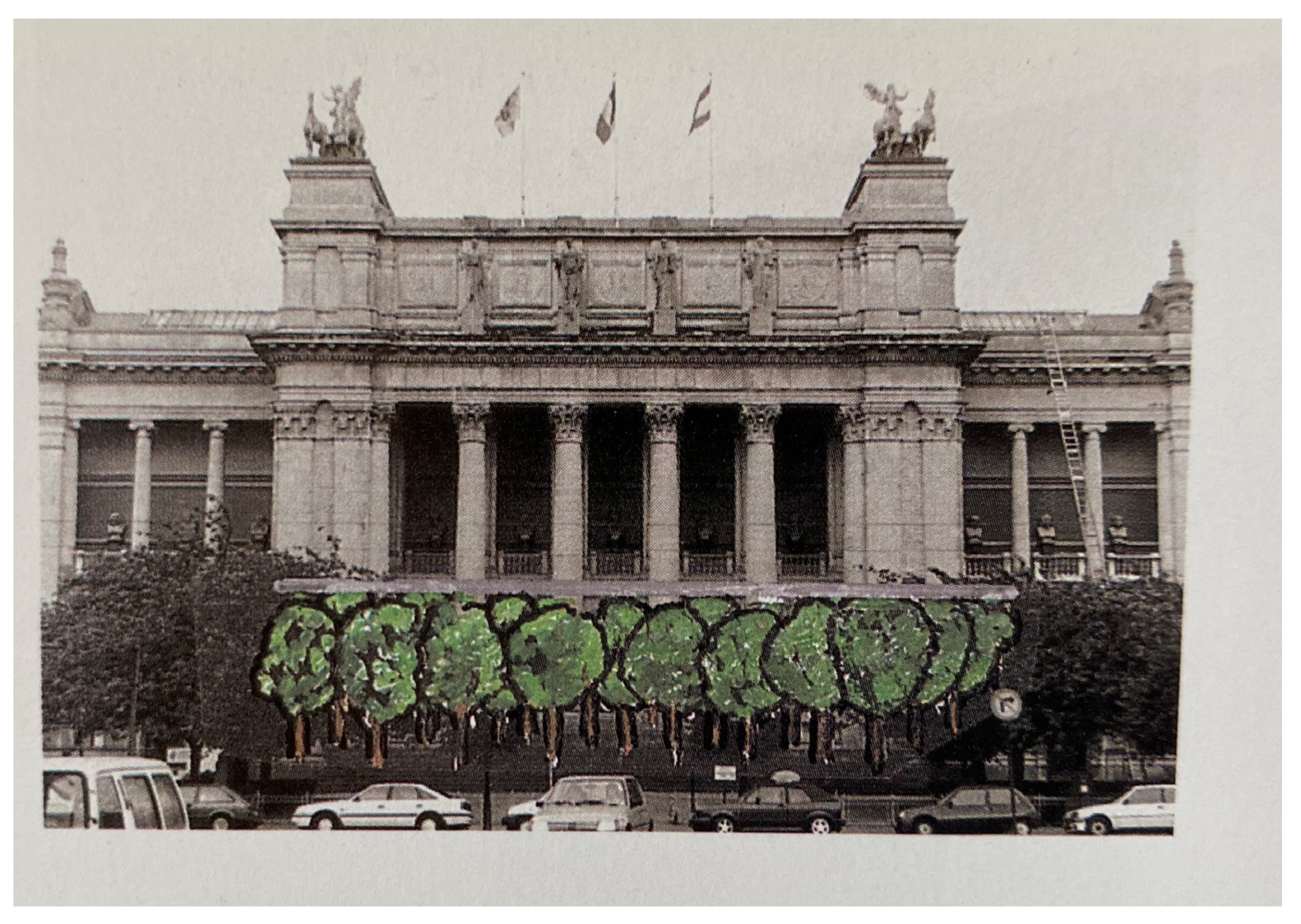

David Lamelas' Quand le ciel bas et lourd was to exist the show'south signature work, given its place in the garden courtyard, centrally before the museum. Knowing his site-specific do, Lamelas did not operate on the premise that art is autonomous and its relationship to its location is incidental. Rather Lamelas consistently forged a loose but witting dialogue between the piece of work and its site, fine art and the social, historical, and political context of its production. Curator Ines Katzenstein refers to this relationship as Lamelas' "situated" practise, in which "the situation in which the piece exists—are the slice's premise."(Katzenstein 2006, p. 78). In the process of developing Quand le ciel bas et lourd, Lamelas' early sketches drawn in Los Angeles from 1987, underwent subtle modifications that tailor the work to its location in front end of the Antwerp museum's master entrance. The work was offset envisioned as copse supporting a hard minimal plate in a neutral setting. A later second drawing (Figure half dozen) situates the work in its new space and specific context, pointing to the obvious clan betwixt the work and the museum'southward exhibition, but also how its understanding is contingent on space (and time). All the same, its realization did not run smoothly. Questioning if the piece of work "is advisable as a face up of the exhibition" and if it would not concenter vandalism, KMSKA director Schoonbaert proposed moving the piece of work abroad from the museum's front (KMSKA 1991e). Eventually, consent was given for the work to be erected on the east lawn of the museum'south classical garden; notwithstanding, the KMSKA stipulated that the trees should be removed afterward the show closes (KMSKA 1991a).

The fraught relation between the museum and the work inappreciably changed later its realization. In fact, Quand le ciel bas et lourd was classified every bit a "problem case" (similar to works by Ana Mendieta, Victor Grippo, Regina Vater, and others), due to a need for increased fencing to protect it from vandalism and eventual oxidation of the metal construction (Schoonbaert 1992, p. 3). Schoonbaert proposed that the work would be donated to either the city of Antwerp or the Flemish customs, and thereafter removed. "Should it residual in its place," she noted, "the pure symmetry feature of the neoclassical, nineteenth-century museum building will be completely damaged. The neighborhood will accept ane more dog toilet—which is, in fact, now already the case." (ibid., p. 4). At the same time, the second program of the work and its eventual location affirms the link between the material configuration of the work and the conditions of the site. On the eastward side of KMSKA'south garden, Quand le ciel bas et lourd resided close to Wide White Infinite Gallery'due south original locations, evoking Lamelas' connection to Belgium as of 1969, and of his being integral to the local conceptual art network—with connections to Broodthaers, the aforementioned gallery, and collectors Herman and Nicole Daled.xxxQuand le ciel bas et lourd's Baudelairean championship is just another echo of the intricate ties between Lamelas, Broodthaers and Kingdom of belgium manifest in the work.

3. Conclusions

Since its construction for the exhibition, Quand le ciel bas et lourd has developed a (discursive) human relationship with its public infinite and the urban center of Antwerp that reasserts Lamelas' relevance to Flanders, Belgium, and their local histories of art. In 2011 it was donated to Antwerp'southward contemporary art museum M HKA, besides in the Zuid neighborhood, an establishment that defines itself equally a "cultural heritage establishment of the Flemish Customs" that "bridges the relationship betwixt creative questions and broad societal bug, betwixt the international and the regional, artists and the public" (1000 HKA 2021a). Within One thousand HKA's collection, Lamelas' piece of work was framed as a memorial to "Flemish art history" and more than specifically, "the international post-state of war avant-garde in Antwerp" (Grand HKA 2021b).

Despite the work's shifting importance and position within Antwerp, it was Flemish Prime number Minister and Minister of Culture Jan Jambon in conjunction with Thousand HKA's ineffective response that ultimately determined its demolition for KMSKA's renovation in March 2021. As i of the leaders of the New Flemish Brotherhood (N-VA), a Flemish-National party founded in 2001, Jambon occupies a platform together with Antwerp'south mayor and N-VA president Bart De Wever that is characterized past a liberal and subtly right-leaning political agenda. Given that Jambon refused to save the work, despite Lamelas' weighty appeal supported past 900 international signatories, the work (and its removal) opens upwardly questions of a wider negligence of transnational heritage by nationalist governments. M HKA, the work'south primary custodian, appeared to have initially underestimated its significance and the potential controversy surrounding the artwork's dismantling. Since so, M HKA has publicly shared its current plans to reconstruct and relocate the piece of work "within the same park, in closer proximity to the one-time White Wide Infinite Gallery" and under a "global curatorial approach for the trajectory of [its] relocation project" (M HKA 2021c).

In 1992 Jean Fisher read Quand le ciel bas et lourd within the contemporary context, every bit a comment on the "crippling exploitation of natural resources (plus the every bit crippling effects of World Bank and Imf demands on the national budgets of Latin American governments)" (Fisher 2012). Lamelas' larger practice, yet, largely evaded such political assertions, preferring an opaque tenor that offers an open-ended significant. In many ways Lamelas' works generate their own identity and remain elusive, hence the title of his 2017 Us retrospective "a life of their own". For this reason, Quand le ciel bas et lourd invites different implications in relation to the 1992 exhibition, simply likewise across its xxx-twelvemonth existence every bit a publicly sited artwork. As this essay argues, this piece of work opens up multiple readings of Lamelas and his do in relation to art in Belgium, from the international avant-garde in the 1960s to postcolonial discourses in contemporary art from the 1990s and recent surges of nationalism in the present mean solar day that might be affecting transnational histories of art in and beyond Flanders. In this regard, Quand le ciel bas et lourd reasserts the integral relationship between Lamelas' practise and his local contexts, notwithstanding transient they may be.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and S.Five.; methodology, Due east.Thousand. and South.5.; formal analysis, E.M. and S.V.; investigation, E.M. and Due south.V.; resources, Due east.Chiliad. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, Due east.Thou. and S.V.; visualization, E.Thousand. and S.V.; projection administration, Due east.Chiliad. and S.5.; funding acquisition, East.M. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Function of this inquiry received funding from the European Matrimony'southward Horizon 2020 enquiry and innovation plan under grant agreement No. 842714.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give thanks David Lamelas and Dirk Snauwaert for their insights during the writing of this article and Jan Mot, Brussels for granting access and permission to the images.

Conflicts of Involvement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Currently, M HKA are working with Lamelas on a reconstruction of the piece of work, which still depends on finalizing a product upkeep and schedule. Run across M HKA's web log mail service from 22 March 2021, available online: https://blog.muhka.be/en/quand-le-ciel-bas-et-lourd-by-david-lamelas-towards-a-sustainable-reconstruction-and-relocation-of-the-artwork/ (accessed on 12 September 2021). |

| ii | Gilissen (1938–), wife to Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976) is now widow and executor of Broodthaers' Estate. |

| three | Lohaus (1940–2010) was as well Anny De Decker's husband. |

| four | Later works such as London Friends (1973) and Los Angeles Friends (Larger than Life) (1976) similarly document his artistic circles. |

| 5 | For more on this work see (Vicario 2019; Quiles 2013; Katzenstein 2006). |

| 6 | For a full clarification of their coming together encounter (Lamelas [2016] 2017, pp. 153–55). |

| 7 | In Paris David Lamelas had links to Argentine exiles Raúl Escari, Lea Lublin and Eliseo Verón, French artist Daniel Buren, critic and curator Michel Claura, and dealer Yvon Lambert. Other cities, such as Milan and Naples, can also be mapped onto Lamelas's European network vis à vis his associations with Françoise Lambert and Lia Rumma. |

| 8 | The Brussels gallery, located in the Galerie Bailli with Gallery D and MTL, opened in 1973 and closed the subsequent year. |

| ix | For more on this history meet (Pen 2015; Richard 2009). |

| 10 | Also referred to as the "magical triangle" in the exhibition catalogue Conceptual fine art in holland and Belgium, 1965–1975 (Héman and Poot 2002) or the "golden triangle" in (Richard 2009). |

| 11 | In Anny De Decker and Bernd Lohaus' interview they repeatedly signal their efforts to break from a distinctly Belgian identity in favor of an international one. This is evidenced in a number of comments, for example their choice to name the gallery "Wide White Space" was perceived as a neutral option. De Decker stated "I didn't want a Flemish name because it was as well provincial; a French proper noun was impossible in Antwerp" (authors' translation). This decision is interesting given the properties of linguistic tension among the Dutch and French-speaking populations in Belgium in the 1960s, which ultimately led to the linguistic separation of the University in Leuven into two in 1968. See (De Decker and Lohaus 1995, p. 21). |

| 12 | Katzenstein quoting Ulf Hannerz, in (Katzenstein 2006, p. fourscore). |

| 13 | Similar the photographs suggest, the original concept was to flick Broodthaers and Lamelas walking towards the camera from the steps of Brandenburg Gate in one continuous, directly shot of three minutes, culminating with a close up of their faces. |

| 14 | The commencement line of Broodthaers' alphabetic character reads: "Conceptual artists are more rationalists rather than mystics … etc …", which equally Benjamin Buchloch points out is an inversion of Sol Le Witt's first line from Sentences on Conceptual Art: "Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists." (Buchloch 1987, p. 97) |

| 15 | Lamelas' move to Los Angeles coincided with the closure of Wide White Space and Marcel Broodthaers' expiry, which collector Herman Daled marked every bit the finish to a vital period. See (Dander and Wilmes 2010). |

| sixteen | It could exist argued that this retrospective interest started as early as 1979 and into the 1980s with the exhibitions Aktuele Kunst in België. Inzicht/Overzicht. Overzicht/Inzicht (1979) at the Museum of Gimmicky Fine art in Ghent and België-Nederland: Knooppunten en parallellen in de kunst na 1945 (1980) at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Nosotros mainly refer to the 1994 exhibition Wide White Infinite: Behind the Museum 1966–1976 at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. It was one comprehensive try to recuperate the period's history through the lens of the Antwerp-based gallery. The show presented archival ephemera, along with works by Wide White Infinite'due south artists, including a section on David Lamelas' Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) and Time as action (Düsseldorf). |

| 17 | Chat with the artist, ten September 2021. |

| 18 | Titled "Encounter between Two Worlds: 1492–1992," the Unesco program was decided upon in 1988. The cynicism of its goal, namely to propagate an ideal of "a unity of the globe" through the commemoration of the 500th anniversary of Europe'due south vehement subordination of the Americas, did non escape its critics. Encounter "executive board decision, October 1988" (Paris: Unesco), 1989, available online: https://whc.unesco.org/ (accessed on 12 Dec 2021). |

| 19 | The history of the Royal Museum for Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA) and its collections date back to the end of the 18th century, when Willem Herreyns, manager of the Antwerp art university, safeguarded a collection of 300 paintings from existence looted from Antwerp's churches, metropolis hall, and mint. The current museum, built in 1890, housed this collection and was jointly run past the urban center and the Belgian state. In 1928 it officially became a land institution. In 1982, following Belgium's second state reform, information technology was transferred to the Flemish Customs. See (Todts 1993). |

| 20 | Encounter as well her "Conquest and the Treason of Images," presentation for the programme Historias de las exposiciones: América—Novia del sol for the Universidad internacional de Andalucía, 2012. Available online: https://www.jeanfisher.com/conquest-and-the-treason-of-images/ (accessed on 10 Oct 2021). |

| 21 | See (Borka 1992b). Schoonbaert had Ana Mendieta's installation Silueta (1973–1981) removed, and Regina Vater's Green (1991) and Roberto Evangelista'south Resgate (1990–1992) altered. According to the reviewer, Latin-American artists felt wronged and quit the vernissage. Schoonbaert'due south deportment triggered Raquel Mendieta and Mary Sabbatino, sister and gallerist of Ana Mendieta, to organize an international protest action and to write an open letter accompanied by a picture of Schoonbaert dragging grasses from the museum. (Information technology remains unclear whether such action and letter occurred.) A museum staff member quipped: "For our director, a proficient artist is a dead artist." (Borka 1992a, p. 17). |

| 22 | Come across, for example (van Mulders 1992; Begehn 1992; Pültau 1992; Brett 1992). |

| 23 | The 70-bespeak plan, in full "Immigration: the solutions. 70 proposals for the solution of the migrant problem," was inspired past French right-wing politician Jean-Marie Le Pen's "Fifty measures to help manage the problem of immigrants." Vlaams Blok called for, among others, the abolition of the Centre for Equal Opportunities and the Opposition to Racism (who, in retrospect, has called the plan "a strategy of ambitious expulsion in order to create a mono-indigenous state"), the exposing and dismantling of the "migrant lobby," and a written report mapping "the costs and balances of the massive migrant presence in our country." Encounter "70-puntenplan (Vlaams Blok),"available online: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/seventy-puntenplan_(Vlaams_Blok) (accessed on 30 October 2021). |

| 24 | Run into also (Vos 1992; Spruyt 1995). |

| 25 | For the promotion of a Leitkultur past N-VA and Vlaams Belang, run into (Scheltiens and Verlaeckt 2021). |

| 26 | Authors' translation. |

| 27 | This text, which accompanies a similar document written by Paul Vandenbroeck, is most surely authored by Catherine de Zegher. |

| 28 | Authors' translation. |

| 29 | Refering to Utotombo, a 1988 exhibition of African art in Belgian collections at KMSKA, Bob van Aalderen rejected inti-coya on the grounds of "bad experiences with such 'strange' titles." See (KMSKA 1991b). |

| 30 | Broad White Space Gallery was located first on Plaatsnijdersstraat i and then Schildersstraat ii in Antwerp until its closure in 1976; both buildings are even so there and were inside meters from where Quand le ciel bas et lourd stood on the KMSKA lawn for 30 years. |

References

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1968. Spleen (89/78): Les Fleurs du Mal. In Oeuvres Complètes. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Begehn, Paul Begehn. 1992. America, Bruid van de zon. Streven, April 1. [Google Scholar]

- Borka, Max. 1992a. Malaise voor de Coloradokever. De Morgen, Jan 31. [Google Scholar]

- Borka, Max. 1992b. Antwerps museum in opspraak: Conservator laat andermaal werk verwijderen. De Morgen, Apr 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bouveroux, Jos. 1999. Nationalisme in Vlaanderen vandaag. In Nationalisme in België: Identiteiten in Beweging. Edited past Kas Deprez and Louis Vos. Houtekiet: Antwerpen & Baarn. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, Guy Brett. 1992. The Undiscovered America. Art + Text 43: 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Broodthaers, Marcel. 1968. Museum in Motion? Museum in Beweging? Amsterdam: Staatsuitgeverij, p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- Broodthaers, Marie-Puck. 1991. David Lamelas: Lavandula, Labiatae, Lamiales. Brussels: Galerie des Beaux-Arts Galerij. [Google Scholar]

- Buchloch, Benjamin. 1987. Open up Messages, Industrial Poems. Oct 42: 97. [Google Scholar]

- Buren, Daniel Buren. 1995. Interview past Yves Aupetitallot. In Broad White Infinite Derriére le Musée, 1966–1976. Dusseldorf: Richter Verlag, pp. 80–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dander, Patricia, and Ulrich Wilmes, eds. 2010. A Fleck of Matter and a Little Bit More. The Collection of Herman and Nicole Daled, 1966–1978. Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther König. [Google Scholar]

- De Decker, Anny, and Bernd Lohaus. 1995. Interview by Yves Aupetitallot. In Broad White Space Derriére le Musée, 1966–1976. Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, pp. 21–81. [Google Scholar]

- Decan, Lisebeth Decan. 2016. Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial: Photo-Based Art in Belgium (1960s–Early on 1990s). Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Jean. 1992. The 'Bride' Stripped Bare. Nevertheless... Artforum 31: 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Jean. 2012. Conquest and the Treason of Images. Bachelor online: https://www.jeanfisher.com/conquest-and-the-treason-of-images/ (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Haidu, Rachel. 2010. The Absence of Work: Marcel Broodthaers, 1964–1976. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Héman, Suzanna, and Jurrie Poot, eds. 2002. Conceptual art in the Netherlands and Kingdom of belgium, 1965–1975: Artists, Collectors, Galleries, Documents, Exhibitions, Events. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Musuem. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenstein, Inés. 2006. David Lamelas: A Situational Aesthetic. In David Lamelas: Extranjero, Foreigner, Étranger, Ausländer. Mexico: Fundación Olga y Rufino Tamayo, pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- KMSKA. 1991a. Tentoonstelling Flandes y América. KMSKA athenaeum. November 18. [Google Scholar]

- KMSKA. 1991b. Verslag vergadering Flandes y América. KMSKA archives. June 17. [Google Scholar]

- KMSKA. 1991c. Verslag vergadering Flandes y América. KMSKA archives. January xvi. [Google Scholar]

- KMSKA. 1991d. Verslag vergadering Flandes y América. KMSKA archives. June 28. [Google Scholar]

- KMSKA. 1991e. Verslag vergadering Flandes y América. KMSKA archives. July 25. [Google Scholar]

- Lamelas, David. 2017. A Nomadic Life': David Lamelas in conversation with Alexander Alberro. In David Lamelas: A Life of Their Ain. Edited by María José Herrera and Kristina Newhouse. Long Beach: Cal Land University Long Beach, pp. 153–69. First published 2016. [Google Scholar]

- K HKA. 2021a. Thousand HKA's Public Mission Argument. Available online: http://www.muhka.be/about-m-hka/mission (accessed on half-dozen October 2021).

- M HKA. 2021b. The Museum's Public Clarification of the Work. Authors' Translation. Available online: https://www.muhka.be/nl/collections/artworks/q/particular/4386-quand-le-ciel-est-bas-et-lourd-when-the-sky-is-low-and-heavy (accessed on vi October 2021).

- M HKA. 2021c. Quand le Ciel Bas et Lourd' by David Lamelas: Towards a Sustainable Reconstruction and Relocation of the Artwork. March 22. Available online: https://web log.muhka.be/en/quand-le-ciel-bas-et-lourd-by-david-lamelas-towards-a-sustainable-reconstruction-and-relocation-of-the-artwork/ (accessed on 6 Oct 2021).

- Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap. 1992. America. Bride of the Lord's day (press release). KMSKA archives. [Google Scholar]

- Pen, Laurence. 2015. Des Stratégies Obliques: Une Histoire des Conceptualismes en Belgique. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Pisters, Ine, and Paul Vandenbroeck, eds. 1991. America: Bruid Van De Zon: 500 Jaar Latijns-Amerika En De Lage Landen. Ghent: Imschoot. [Google Scholar]

- Pültau, Dirk. 1992. Retrospect: America, Bride of the Dominicus. Museumjournaal 3: 5, n.p.. [Google Scholar]

- Quiles, Daniel R. 2013. My Reference is Prejudiced: David Lamelas's Publication. ArtMargins x: 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynebeau, Marc. 1995. Het klauwen van de Leeuw: De Vlaamse identiteit van de 12de tot de 21ste eeuw. Leuven: Van Halewyck. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Sophie. 2009. Unconcealed: The International Network of Conceptual Artists, 1967–1977. Edited by Lynda Morris. London: Ridinghouse. [Google Scholar]

- Scheltiens, Vincent, and Bruno Verlaeckt. 2021. Extreemrechts: De Geschiedenis Herhaalt zich niet (op Dezelfde Manier). Brussels: ASP Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonbaert, Lydia. 1992. Kunstwerken 20ste eeuw: America. Bruid van de Zon. KMSKA archives. May 10. [Google Scholar]

- Snauwaert, Dirk. 1997. David Lamelas: A new refutation of time. In David Lamelas: New Refutation of Time. (Kindle edition). Dusseldorf: Richter Verlag, n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Spruyt, Marc. 1995. Grove Borstels. Stel dat het Vlaams Blok Morgen zijn Programma Realiseert, hoe zou Vlaanderen er dan Uitzien? Leuven: Van Halewyck. [Google Scholar]

- Todts, Herwig. 1993. Het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten te Antwerpen. Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen 31: 2. [Google Scholar]

- van Mulders, Wim. 1992. Amerika—Bruid van de Zon. De Witte Raaf 37 May–June. Available online: https://world wide web.dewitteraaf.be/artikel/item/nl/223 (accessed on 10 December 2021). 37 May–June.

- Vandamme, Erik. 1991. Nota i.v.m. vergadering 28.6.91: 'Ver gezocht en ver van goed. KMSKA archives. July i. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten, Diane. 1989. Nota betreffende de tentoonstelling 'Flandes y America'. KMSKA archives. May. [Google Scholar]

- Vicario, Niko. 2019. The Thing of Circulation: Teletype Conceptualism, 1966–1970. In Conceptualism and Materiality, Matters of Fine art and Politics. Edited by Christian Berger. Leiden: Brill, pp. 213–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, Louis. 1992. De politieke kleur van jonge generaties. Vlaams-Nationalisme, nieuwe orde en extreem-rechts. In Herfsttij van de 20ste eeuw. Extreem Rechts in Vlaamnderen 1920–1990. Edited by R. Van Doorslaer. Leuven: Kritak, pp. fifteen–46. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1. David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the heaven is depression and heavy), 1992. Installation consisting of metal sculpture and trees on inclined surface. 6 × xx × 7.8 m. Collection G HKA, Museum of Contemporary Fine art Antwerp. Photo: David Lamelas. Courtesy of the artist and January Mot, Brussels.

Figure one. David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the heaven is low and heavy), 1992. Installation consisting of metal sculpture and copse on inclined surface. 6 × 20 × seven.eight m. Collection M HKA, Museum of Contemporary Fine art Antwerp. Photograph: David Lamelas. Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Figure ii. David Lamelas, Antwerp-Brussels (People + Fourth dimension), 1969. Black and white photograph, 29.5 × 23.5 cm. Photo: Maria Gilissen. Courtesy of the artist and January Mot, Brussels.

Figure 2. David Lamelas, Antwerp-Brussels (People + Time), 1969. Black and white photo, 29.5 × 23.5 cm. Photo: Maria Gilissen. Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Figure iii. David Lamelas, Antwerp-Brussels (People + Time), 1969. x black and white photographs, 29.vii × 23.6 cm each, 31.5 × 26. × 2 cm (signed and numbered portfolio). Edition of 10 (of 7 produced editions). Installation view, On Kawara, David Lamelas at Jan Mot, Brussels, 2019. Photograph: Philippe De Gobert. Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Figure iii. David Lamelas, Antwerp-Brussels (People + Time), 1969. x black and white photographs, 29.seven × 23.6 cm each, 31.5 × 26. × 2 cm (signed and numbered portfolio). Edition of 10 (of 7 produced editions). Installation view, On Kawara, David Lamelas at Jan Mot, Brussels, 2019. Photo: Philippe De Gobert. Courtesy of the creative person and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Figure four. David Lamelas, Tree Inside a Glass House, 1990. Watercolor on paper, 44.five × 36.5 cm. Reproduced in the exhibition catalogue Lavandula, Labiatae, Lamiales, Galerie des Beaux-Arts Galerij, Brussels, 1991. (Broodthaers 1991, n.p.). Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Figure 4. David Lamelas, Tree Within a Glass Firm, 1990. Watercolor on paper, 44.five × 36.5 cm. Reproduced in the exhibition catalogue Lavandula, Labiatae, Lamiales, Galerie des Beaux-Arts Galerij, Brussels, 1991. (Broodthaers 1991, n.p.). Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

Effigy v. Exhibition plan of America: Bride of the Sun—500 Years of Latin-America and the Low Countries, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), 1992. Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp archives ref. Exist-A4001/kmska/KMSKA/13.

Figure 5. Exhibition programme of America: Bride of the Dominicus—500 Years of Latin-America and the Low Countries, Imperial Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), 1992. Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp archives ref. BE-A4001/kmska/KMSKA/13.

Effigy 6. David Lamelas, Initial proposal for the location of the work at the main archway of the KMSKA (not realized). Drawing on photo of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp reproduced in the exhibition catalogue America, Bride of the Dominicus, 500 years Latin Amerca and the Low Countries, 1991, KMSKA (Pisters and Vandenbroeck 1991, p. 244). Courtesy of the creative person and January Mot, Brussels.

Figure 6. David Lamelas, Initial proposal for the location of the piece of work at the main entrance of the KMSKA (not realized). Drawing on photo of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp reproduced in the exhibition catalogue America, Bride of the Lord's day, 500 years Latin Amerca and the Low Countries, 1991, KMSKA (Pisters and Vandenbroeck 1991, p. 244). Courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels.

| Publisher's Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Artistic Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/).

0 Response to "Why Was Stymi and Bruno the Most Interesting Failures in Language Arts"

Postar um comentário